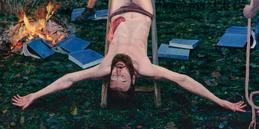

Aris Kalaizis: "The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew or the double Martyrdom"

In this text describes the German-American author Paul-Henri Campbell the reception history of the St. Bartholomew at the example of Kalaizis' large-size painting. In addition, he examines the religious Impetus within the "Leipzig School".

In January 2015, the Greco-German painter Aris Kalaizis completed a large-scale oil painting that shows the martyrdom of St. Bartholomew. The ideas informing that work of art have been inspired by the long history of adoration regarding that saint at the Imperial Cathedral in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. From the gothic period on, especially after a relic of Bartholomew was brought to the city, the Biblical narrative as well as medieval lore have encouraged the fabrication of numerous depictions of the martyr within and around the cathedral.

»The Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew or the double Martyrdom« is a contemporary interpretation that confronts thirty-three depictions of the martyr at the Imperial Cathedral. As we shall see, the painting contests the very claim that the Catholic Church makes on the shoulders of its canonized celebrities. We shall furthermore see that in doing so this painting uncovers something central to the phenomenon of religious faith itself.

Aris Kalaizis's approach to St. Bartholomew is remarkable on multiple levels. To begin with, it is the first time a member of the ›Neue Leipziger Schule‹ has worked in direct confrontation with an ecclesiastical structure in Frankfurt am Main. Secondly, the painting augments the religious theme of martyrdom by incorporating elements derived from recent German history. It blends hagiography with contemporary historiography, for instance, by referring to the Nazi book burnings on the nearby Römerberg in 1933. Finally, the theological motif of Christ's Passion, which the martyr imitates in his suffering, is central to this new painting — even though this may seem natural, it isn’t exactly what most of the other depictions do and what makes Kalaizis' painting noteworthy, as we shall see.

Aris Kalaizis, Religion, and the ›Neue Leipziger Schule/New Leipzig School‹

First, let us look at Aris Kalaizis in the context of his artistic roots in Leipzig as well as contemporary German art. After the Iron Curtain era had come to an end and with it the GDR, a young generation of artists challenged the aesthetic dominant in West Germany by insisting on a critical affirmation of the canon. The Academy in Leipzig originally was specialized in visual arts related to book making, but began to rival other East German academies in Dresden and Berlin, when Bernhard Heisig introduced classes in painting to the curriculum in the 1960s. These young men were for the most part born during the 1960s in East Germany. They were the second generation of (figurative) painters who had come from the Academy. Their crucible was the city of Leipzig, and they proudly traced their roots to the Academy of Visual Arts (›Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst‹).

Throughout the 1990s, they reinvigorated techniques used by the Old Masters, even though the West German abstract schools declared figurative painting dead. In defiance of self-proclaimed avant-gardists, they focused on skill and craftsmanship, as it had been the understanding of Duerer, El Greco, Ribera, or Velázquez. Thus, the ›Neue Leipziger Schule‹ quickly found its audience by bringing new ideas to classical approaches to the art form. They pushed for innovation without discrediting the past and thereby did not degenerate into the hypothermic cynicism that ultimately – today – left their competitors bitter and barren.

Reflecting on the Leipzig School, one should not, however, consider a single generation in isolation. This is particularly important, when one considers their artistic approach to religious themes. For members of the ›Old‹ Leipzig School, though no strangers to religion, had struggled with religious themes and motifs under a Communist régime and in the climate of systemic atheism, which that régime had created. Even though the Leipzig area had historically, of course, been the heartland of the Reformation, the ideological rationale of 20th century East Germany was Communist, until Reunification in 1991. Artist born shortly before or during World War II dominated the ›Old‹ Leipzig School. It was that group of artists by which the generation of Kalaizis was introduced to painting at the Academy. His generation learned from Werner Tübke's monumental ›Bauernkriegspanorama‹ in Bad Frankenhausen (1976−1987) as well as his ›Zellerfelder Altar‹ (1997); or from Bernhard Heisig's ›Neues vom Turmbau‹ (1977); or from Arno Rink's ›Italienische Begegnung‹ (1978). All the works just mentioned deal with religious matter in one way or another.

Tübke's or Rink's interest in religion was partly ideologically, partly existentially motivated. Viewing their work in retrospect, one is astounded by the amalgamation of rationalistic critique of religion and somber obsessive fascination with religion. Artists in that earlier generation of the Leipzig School frequently combined their critique of religion with a critique of authoritarian government. They rebelled against religion as much as they utilized religion in their rebellion against a Socialist government, which they feel discontent about.

Although the older generation of Leipzig School artists rejected the Christian faith, for political or other reasons, and although most artists from the younger generation received an atheist upbringing (as it was typical in socialist countries), painters such as Neo Rauch, Michael Triegel, Bruno Griesel, or Aris Kalaizis are not at all deaf to the powers unseen. On the contrary, their curiosity and lust and yearning for transcendence is much more vibrant and fresh and apparent, than their Western counterparts, even though the religious institutions remained generally intact in places like Bolzano, Vienna, Zurich, Munich, Cologne, Düsseldorf, or Hamburg.

Even though the atheism of an East German childhood may have alienated them from traditional forms of liturgy and religious practice, the history of art brought religious themed images to them. Thus their unique and productive perspective, unparalleled in the secular society of Western democracy. It is necessary to understand that these young men did not see a contradiction between the new and the old, but rather saw a rupture, forever ineffaceable.

They moved toward this chasm like strangers, like amazed children. Although they are full aware that the 21st century isn’t the 11th or the 17th century, the artists associated with the ›Neue Leipziger Schule‹ are united in striving toward technical perfection, use of perspective, and figurative composition. The spirit of Rubens and Michelangelo is evident everywhere in their work. But they are not naïve invigorators of somewhat rare, somewhat antiquated techniques and ways of thinking; instead, they are eye to eye with the radical transformations that took place throughout the 20th century in painting as well as in our views concerning the status of painting.

Unlike the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England or the Nazarenes in Austria, painters from Leipzig do not celebrate their stylistic inheritance and indebtedness in the sense of antimodernist protest. Their intention is not a restitution of the past, but an attempt at making the pastures of the past arable for the seeds of tomorrow. Thus their yearning is not nostalgic, thus their enormous modernity. This is why they have not grown bitter in stubborn revolt, but rich in productive vision.

Aris Kalaizis occupies a special place in the unfolding history of the ›Neue Leipziger Schule‹. Born in 1966, he grew up in Leipzig as the son of Greek immigrants. His path to painting was long; and it was an unlikely path. His father and mother belong to the throngs of ten-thousands of children who have been forcefully separated from their parents after the Greek Civil war and have been deported to Soviet controlled countries, such as the GDR. His parents later worked in the graphical industry in Leipzig. His position of otherness already begins here.

One should not underestimate what it meant to grow up in an immigrant family within the homogenous fabric of East German society in the middle of the past century. Being different — to be different: because your true origin is where Apollo strives against Dionysus, because you truly come from where Pan rustles among the oleander and cypress groves, and where some forlorn nymph seems to be winking daintily at every rippling sweet water spring. His life's story can hardly be told. After it has been written down, it will seem as though it was invented or dreamt up.

…what is Sottorealism?

We will hear of a small boy playing soccer on the outskirts of Leipzig during the early 1970s. We will hear how he dashed towards the goal but suddenly came to a full stop, his abandoned ball rolling on, because he was suddenly overwhelmed by some distant scene that came into his sight, his captivated gaze arresting his entire body in midfield.

The reality, in which Aris Kalaizis came of age, was radically different from the socialization of his thoroughbred German peers. Nevertheless, it was the reality in which he initially became an apprentice in the printing industry and was trained in commercial offset printing. It was the reality in which his father build him his first easel of spare woods and gave it to him for Christmas; and in which his mother bore the scent of foreign herbs and spices, while the other children were forced to eat Saxon and Thuringian specialties for lunch.

Looking back at this vanished world of the GDR, in which everybody seemed to be more or less complicity accommodated with the warped framework of Socialist reality, one isn’t surprised that, after German Reunification in 1991, Aris Kalaizis decided to henceforth frame his own images of the world. One is no longer surprised to learn that he henceforth picked the frame-size he thought fit for his vision. We are no longer surprised that his artistic oeuvre insists on the autonomy and multifaceted nature of what we see.

And thus he goes forth and knocks upon the gates of the famous ›Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst‹. He is admitted. He soon becomes the master student of Arno Rink. He then founded a gallery with some friends, the maerzgalerie. They quickly become successful. His paintings are soon bought by collectors all over Germany, Austria, France, the Netherlands. He is invited to New York City, then tours China. His story is no fairytale. It is quite real. But it must be told like a fairytale, for it was unlikely.

It was an American art historian, many years later, who realized that we need new categories in order to understand his work. In studying his artwork, while he spent a year in New York City, Carol Strickland coined the term ›Sottorealism‹ in order to apprehend what his happening on his canvas.

…it's a brand of metaphysics that is in love — that adores this world's mortal coil

What is ›Sottorealism‹? Think of the musical term ›sotto voce‹: a gentle, whispering way of speaking. Sotto voce: Mozart's scores are full of it. Sottorealism: it denotes the murmurs beneath and above reality. Dissonance. Glistening. It is a brand of metaphysics that is in love — that adores this world's mortal coil.

Acknowledging that what we see is not realism, as it was in fashion during the 19th century, nor any variety of surrealism. What Strickland saw, was some new hermeneutic. Certainly, there is in almost every Leipzig School painter (old or new) a grain of that carefully guarded, distrustfully shielded in-the-closet spirituality known from the revolutionary Russians, from Soviet art, which, in order to be consistent with its Marxist dogma, would not admit that there was a desire for transcendence creeping in along the seams.

Even though Sottorealism denotes a perspective beyond realism and surrealism, it is also beyond the occasional effervescence of grace. Sottorealism operates in the rationale of dreams, nightmares as well as daydreams, it makes use of reveries, modes and states of intoxication, trance, madness and fury, but it is not itself a depiction of dreams, reveries, trance, madness, fury. Instead, it gives us a reality that is influenced by such modes of perception. These degrees of irrationality weigh upon the reality that is depicted. They delude that reality. But Sottorealistic reality always stays as real as a polluted lake stays a body of water, however many toxins and counter-toxins we might pour into it.

St. Bartholomew at the Imperial Cathedral – Existing Artwork and New Discoveries

In the cathedral's orbit there are at least 33 depictions of church's patron saint in various artworks, ranging from oil painting to fresco painting, from sculpture to vasa sacra and liturgical vestments. In the course of his first exhibition at the ›Dommuseum Frankfurt‹, which showcased oil paintings such as ›Make/Believe‹ (2009) and ›The Silence of the Woods‹ (2010), Aris Kalaizis became intrigued by the local cult of St. Bartholomew and began to immerse himself into the apostle's life and works.

Kalaizis, however, did not primarily study the numerous hagiographical sources that give (occasionally contradictious) accounts of his missionary work in India and Armenia. Instead, he carefully meditated over the aforementioned material witnesses at the cathedral, its artwork.

Certainly, the Kalaizis is aware of the Biblical references to Bartholomew offered by Matthew (10:3), Mark (3:18), Luke (6:14) as well as the Acts of the Apostles (1:13). He is informed about the fact that the Evangelists use the Aramaic bar-Tôlmay (son of the ploughman) as well as Nathanael (gift of God). The painter realized the extent of the missionary's voyages: allegedly, he visited India, the land of the Medes and the Persians, Syria, Germania, the Parthians, even Armenia.

Collecting the lives of the saints, the mediaeval book ›Legenda aurea‹, compiled by the Dominican scholar Jacobus de Voragine (1230−1298), gives a detailed account of St. Bartholomew's life. This ›Golden Legend‹ was even more popular during the Middle Ages than the Bible itself. Its novella-like narratives or Vitae, rich in detail and imagination, have become central to western art. The ›Legenda aurea‹, in any case, tells us the story of a preacher who raved against the adoration of heathen deities or their graven images. It also tells us the story of Bartholomew, healing the daughter of a heathen king by dispelling evil spirits. Another story entails the nefarious command given by local elites, ordering him to be flayed and skinned alive. But this is not the only story regarding his martyrdom. For even though the punishment of skinning a human being was predominately used in ancient Persia, it was not the only narrative about his martyrdom: other sources speak of a crucifixion with his head pointing downwards (like St. Peter's), about him being dumped and drowned in the ocean, some speak of a beheading.

As soon as we compare the sources critically, a wide field of contradictions opens up, which is, of course, quite common in Christian hagiography or for that matter in any type of tradition carried over large periods of time by a forever shifting and transforming culture. The Western canon is a motley phantasmagoria of lore, law, lilts, and lullabies laboriously passed on by letter, lip, and rite in a constantly fluctuating pageant.

The history of piety and adoring the apostle Bartholomew in Frankfurt am Main begins at least when the relic, a calotte-like fragment of a human skull (12 cm by 7 cm), is transferred to the city. In 1215, a seal was attached to a deed concerning the local collegiate chapter that shows the saint. Some historians even believe the relic had been already brought from S. Bartolomeo on the Tiber Island in Rome to Frankfurt am Main in the mid-12th century. In order to adequately present this precious relic, various reliquaries have been commissioned.

…of a crucifixion with his head pointing downwards (like St. Peter's), about him being dumped and drowned in the ocean

I'd like to briefly discuss two of them. Franz Ignaz Berdold, a goldsmith from Augsburg, created a reliquary bust in his workshop that is dated circa 1727. In a frontal perspective, we are presented with the ascetic head of a bearded man with head hair hanging down onto his shoulders in gentle curls. His neck and chest are of muscular complexion and have been shaped with great plasticity. His figure is accompanied by some sort of cloth that is draped over his shoulders and gives the bottom of the bust calm, cohesive contours. It is a so-called ›speaking reliquary‹, as its form hints at that which is stored within it. Berdold's baroque bust dramatizes the beauty of the human body and thus creates a climactic tension between the beauty of created things and the vile cruelty inflicted upon it by heathen henchmen. Especially, by the way, the drapery is reminiscent of the heroes, demigods, and gods of the classical period.

The second reliquary, I'd like to discuss at this point, was created in 1929 by the Frankfurt-based goldsmith Karl Borromäus Berthold and was made using gilded silver and various gemstones. The object should be viewed in the context of the arts and crafts movement that started with the Jugendstil movement. The reliquary rises from its tiered base, upon which a triangular shrine is placed. The general form, of course, is heavily indebted to Expressionism and bears remnants of a late neo-Gothic style. Three column-like berg-crystals are mounted to the steps on each side leading up to the gable of the triangular capsule, above which a polished Cross is towering, also made of diaphanous berg-crystal. The entire shrine is unified by the mandorla (or almond shaped) aureole, arching over the reliquary. Around the base we read on the frieze: »SANCTE + BARTOLOMAEE / PATRONE + ET / PROTECTOR + NOSTER / ORA PRO NOBIS«. I think it is quite apparent that both reliquaries are centralizing the holiness of the martyr, not his suffering.

The overwhelming majority of the 33 depictions of St. Bartholomew, scattered throughout the building, follow the rationale just mentioned. The great monstrance with its spiry architectural form (ca. 1498) shows a little silver figure of the apostle, holding a knife in the right hand. The little figure, clearly depicted with a halo, is exalted beyond its temporal suffering and is holding a book in his left hand. Another object, a clasp or pectorale, designed to hold liturgical vestments in place, shows the saint with his skin draped over his slightly bent arm.

Let us examine this form a bit closer: St. Bartholomew with his skin draped over his arm, boasting the knife that was the instrument of his suffering. It is repeated often throughout the cathedral – for instance in the oak carving on the choir stalls (ca. 1352), or in the colorful sandstone sculpture mounted on the northern wall of the choir (ca. 1440), or on the plate of the capstone that concludes one of the western vaults in the Wahlkapelle (Election Chapel, ca. 1425 – 1438). In addition, we find this triumphant form of St. Bartholomew, the saint who never seemed to be harmed by martyrdom, on various altars along the transept: the relief figure on the left wing of the Sacred Heart Altar (Memmingen, ca. 1505), for instance, or the sculpture in the crowning woodwork above the Altar of Our Lady (Swabia, ca. 1500).

But it is the famous St. Bartholomew frieze that covers most of the southern and northern walls of the choir which gives a most glorified account of the martyr's fate and triumph. The style and mode of narrative adopted in the 28 large-scale scenes of the frieze celebrates his holiness and mediaeval Christianity's later perception of having attained ultimate victory over heathendom. The frieze follows the ›Legenda aurea‹, as is apparent in dressing St. Bartholomew in a white robe. The secco painting with tempera was commissioned in early 15th century on the account of a donation made to the chapter. It offers a narrative that begins with St. Bartholomew being sent out to the spread the gospel along with the other apostles and ends with a heathen prince being made bishop, after he converted to Christianity. The frieze is essentially about the origin of the Church. It also, one might add, already presupposes the concept of discipleship, too, which is perhaps an unwarranted, even hasty claim, as we shall see. It looks like most of these prominent depictions are much more concerned with the Church than with Christ. One might argue at this point, »Of course these depictions are predominantly concerned with the Church, but not because they are ignorant of Christ, but because they are Catholic «. I think arguing like this would be cynical.

Take, for instance, Oswald Ongher's oil painting ›Agony of St. Bartholomew‹ (ca. 1670) that is mounted on the western wall of the northern aisle. In the middle of the picture we see Bartholomew leaning against a tree, merely dressed in a waistcloth. He is exhausted. One of the three henchmen surrounding him has evidently tied him to that tree. Holding a knife in his mouth, we see another henchman to the right. He is just pulling off Bartholomew's skin. He has already done so on both arms. We see the maltreated muscle parts, the blood trickling down from his armpit. In front of that group, we see another figure in the foreground adorned with feathers, a sign of his heathen nature. He is running his blade across the sharpening steel. In the right corner, in the background of the picture, we see Astyages, the brother to the heathen king, decorated with laurels watching with his soldiers. The paining, the only surviving fragment of a Baroque altar destroyed in aerial bombardments during World War II, contrasts Bartholomew enduring his agony with the sardonic cruelty, glee, and cynicism of the three underlings of Astyages (himself only brother of a king) tormenting the unknowing, unassuming, patiently enduring man of whom we will realize that he was a saint.

This is the vision that Aris Kalaizis will carry forth and develop in his interpretation of Bartholomew's martyrdom. While Bartholomew is often found in religious art standing, his skin draped over his arm, it is necessary to realize the ex post facto depictions, showing the saint in his sainthood, is somewhat anticlimactic. Ongher and Kalaizis point at another tradition of looking at saintly faith: a painful mode of faith, a faith that has retrained a sense of the forlorn tragedy that is the actual horizon of suffering. Consider, for instance, the painting of St. Bartholomew (1617) by the Baroque painter Jusepe de Ribera. The picture today is on display at the Prado in Madrid. Bartholomew is suspended from a hanging wooden beam like a sail, while the henchmen are getting ready to inflict their agony upon him. Also, consider the medieval Weltgerichtsaltar (Judgment Day Altar) at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum by Stefan Lochner.

…no trace of good news

Nowhere a sign of grace. No trace of good news. There are no acts of charity: nobody walks again, sees again. Nobody is being fed. Nobody is being found or saved or restored to life. No one is walking across waters. The kingdom, lost. The heavens, empty. And if we take to heart what is actually happening in this scene here, if we look at what human beings are inflicting upon their fellow creature, then there really isn’t any credible evidence for glad tidings of joy. Nothing in this scene seems to corroborate the gospel's message of hope.

Of course, it is bewildering to look at this painting without activating the cultural information stored in the back of our brains. Because the evangelists assure us: his name was Bartholomew. He was an apostle, one of the Twelve. Lore tells us: he was in India or Persia or Armenia – where he met Death. But we should be cautious, for Aris Kalaizis isn’t going to do us a favor. We cannot step in front of this painting pleased with all our enlightened knowledge, ready to relish an aesthetic bonbon. We cannot come, as though naïve, as though guileless, as though innocent, respectable, knowing — as though unblemished. This is not a painting that bathes us in sunlight: it is not a painting that will mirror our sophistication.

This is ground zero. He failed. He died. Church tradition, which is always so quick with its armory of terminology, rashly calls his fate martyrdom. Martyrdom, as though there were no question about it. Martyrdom — a mere lexical item, a term, a word. But what's a word after all? We need to be very clear: here we have got a missionary — a believer — shown in the moment of his total failure. He is shipwrecked. Whatever his intentions, they are burning and crashing. Whatever he wished to bring to these witless heathens, it only had a slim chance anyway, it was hanging by a thread, and the henchmen are putting their knife's blade to that thread. Now, they are cutting through, severing it. It's over.

And doesn’t this version of the story or this emphasis, doesn’t it unmask those triumphant depictions, I discussed above, those depictions … so handsomely strewn about in the dainty blissful dominion of Frankfurt's principal Cathedral? Doesn’t this triumphant pose suddenly seem a bit complacent? We have it made. We're saved. Doesn’t this depiction of martyrdom seem like an impotent, stubborn stance against an ignorant, violent, ultimately adverse world? So what does it mean to »own« a relic of a saint, anyway? Or, for that matter, what does it mean to possess the story of a saint's life? Or to »decorate« our hallowed walls with a painting or a sculpture of a saint? Is the relic the ultimate gimmick, the proof that it is all true: a fragment of a man's skull? Does it testify to everything? That it all went well in the end. That it's all good. That we may rest assured. That we may be blissful. That we may believe. Amen?

…will happen upon some token of hope

There is something amiss. For when we read in the Life of St. Bartholomew carefully, we encounter something strange in the ›Legenda aurea‹. At one point, it says: »There is no consensus of opinion with respect to the way in which Saint Bartholomew was martyred«.

Aris Kalaizis will not flatter the Church with another glorious depiction of one of her martyrs. When we turn to his earlier paintings, we will search in vain for a redeemed world. On the contrary, we will see broken down walls, exploited landscapes, or abandoned buildings canvas after canvas. We will witness disturbing scenes of destruction, desolate, utterly broken situations.

Here or there, perhaps, we will happen upon some token of hope, as in the colors coming through the dark tumorous clouds making up the horizon shown in this painting. Nevertheless, hope in his paintings is bitter. It isn’t some sort of romantic, kitschy, kowtowing hope handed out by those in the know. Instead, it is hope that is hard to bear. Because maybe what you are seeing on the horizon isn’t a rosy-fingered dawn, but the last flashes of light in the offing before the night.

Double-binds: erroneous messages in the face of truth, true messages in the face of error. Uncertainty. Bitterness. Hope that is hard to bear, despite the knife in your flesh. Affirmation even at ground zero, in the face of absolute nothingness and failure, suffering in the face of and because of that God who loves you. Zero consolation. None. Nowhere. So, actually it is perverse.

…this painting is presented in the Imperial Cathedral in Frankfurt, only about 200 meters away from the Römerberg where the Nazis burned books in 1933

Mark carefully: what we are looking at, is sheer perversity. We are taking the stable ground away from our tradition, and we are replacing it with a double bottom. It is an unbelievably perverse, impertinent vision of hope. This is its eminent greatness. Its bamboozling realism. I will come back to this point at the end of this essay. The greatness in the vision of Aris Kalaizis is this: he has understood that the world is forever unfinished.

The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew: faith as uncertitude. Remember, the ›Legenda aurea‹ at one point says: »There is no consensus of opinion with respect to the way in which Saint Bartholomew was martyred«. This painting offers us various interpretations also found in the various accounts that relate the Life of St. Bartholomew, the Vitae. Crucified head down. Skinned. Beaten.

But perhaps losing his life isn’t the most terrible aspect of his agony. Isn’t burning the book and the news that it entails far more terrible, unbearable indeed, than dying? Holocaust, burnt whole. This painting is presented in the Imperial Cathedral in Frankfurt, only about 200 meters away from the Römerberg where the Nazis burned books in 1933.

Or: take a look at the ruined church in the middle of the picture. The ruined edifice does indeed exist, on the outskirts of Leipzig, in a village named Wachau. The church in Wachau was ruined during the bombardment of Leipzig in World War II and later neglected by the communist régime. The architect of the ecclesiastical structure was Constantin Lipsius, a famous Saxon architect of the late 19th century. Lipsius, however, did not only build churches, but also the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig, which is now the prestigious Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst.

Is hope justified? Maybe. Maybe not. Reality has more ambiguity than you can stand. And there now, in that moment, when all seems lost, one of the henchmen breaks loose — breaks out of his role, grabs the book, and turns his back on this horrific situation. He steps into the sea and raises the burning book, towards whatever is in the background of this painting. But: we do not know if it is his mockery of the gospel, his final ridiculing of Bartholomew's book; we don’t know if he is revolting against it in an act of grotesque negation. Or is he revolting against the enormous negation that is dominating the picture?

There it is. Now, we may see it. We are looking right at it, the bitterly undecided, ambiguous, because forever incomplete hope, of which nobody actually could say if the man holding the burning book is praising or ridiculing hope. We do not know if he is raising it towards a rosy-fingered dawn or towards a twilight foreshadowing some terrible, infernal night. We do not know if this painting is about God or about art. We do not know if this painting is about evil or about salvation. Everything is left open, undecided and appallingly ambiguous. Nothing can be said with certainty, and this is, to say the least, utterly unbearable.

…Faith as an uncertainty. This is more an agnostic and no atheistic beginning

Perhaps, this is the point, at which we might understand why it isn’t enough to have faith in what is shown by the frieze in the cathedral's choir. The St. Bartholomew frieze alone isn’t enough. We shouldn’t accept its apparent unambiguity, its supposed clarity and perspicuity, for we must look at the moment of negation, nothing has been established, and nothing has been achieved, all is at peril, always.

The only thing we have is art that is art before the establishment of all academies; all we have faith that precedes all material structures of its institutions. We have a burning book, held into uncertainty — ambiguous, dark, searing, and utterly unbearable. We have the revolt of undecided meaning, the uproar and clamor of bitter hope that runs hotly through our veins, before even one altar has been consecrated that may impart the word ›martyrdom‹ upon us.

It seems unbearable that the church, in the background of this scene of extreme violence, is left in ruins. It seems unbearable that the henchmen, to whom Bartholomew wanted to bring Good News and whom he wanted to bring together as a church, are rejecting him. We know the matrix for this type of rejection. But whoever says a consoling word of reconciliation now, is a liar. It isn’t easy to kneel in Gethsemane.

But whatever is on the rocks here, whatever is at peril here, is not the church, not an academy, not this or that martyr or artist, but what is on the rocks, what is hanging on a thread, is the advent of good news. What is at peril, is the possibility to wring hope from all of this in the face of annihilation.

©2015 Paul-Henri Campbell | Aris Kalaizis

Paul-Henri Campbell was born 1982 in Boston.The German-American author studied Classical Greek and Roman Catholic Theology at the National University of Ireland and at the Goethe-University in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Currently, he is completing his PhD at the Jesuit College Sankt Georgen in Frankfurt am Main. He writes poetry and prose in German and English. Since March 2013, he is a member of the editorial board of one of largest poetry magazines in the German language, DAS GEDICHT. Publications include ›meinwahnstraße‹ (2011); and three books of English and German poetry: ›duktus oprandi‹ (2010), ›Space Race‹ (2012), and ›Am Ende der Zeilen. Gedichte/Poems‹ (2013).