I Have Nothing to Say - Perhaps That is Why i Paint

Aris Kalaizis on painting in times of crisis, the social relevance of art, and the humbleness of beginning. An Interview between Stephan Schwardmann and Aris Kalaizis

Schwardmann: We commence our discussion in an atmosphere of general disillusionment regarding our surroundings, which used to be perceived as relatively stable – such as nature, our affluent society, or (global) political configurations – yet which appear to have suddenly begun to erode. The visual arts have always had the ability to cut through the certainties of our perception, and they have thus established a long tradition of persevering in the face of irritating ambiguity without collapsing.

Is the artist, or rather is artistic creation able to depict a possibility of introducing the concept of “bewilderment” as an element of normality in a positive light into our current mind sets and mental deadlocks.

Kalaizis: As we know from the most recent history of the 20th century, art has often taken on a compensatory character and has thus frequently paved the way toward the different, toward the new. In principle, art has always acted as a kind of cipher code for life in society, regardless of whether the artist accepts or rejects the complex of problems associated with existence in society. The rejecters, in other words those who have had no desire to enter into a race with reality, have often been able to impart a more subtle mood of their times within their texts or pictures.

S: Perhaps I should rephrase my question. You take the position that the artist should stay with his brushes, that he can (de)code most effectively from a distance. Nobody wants to politicize aesthetics – d’accord. I would like to ask – going beyond all the pseudo-relevant news regarding the market value of paintings and pieces or art or regarding their ornamental utility – whether art and along with it whether the artist himself shouldn’t get involved in the structuring of a civil society – in public or interdisciplinary discourses, community and/or school projects, etc.

K: You raise the issue of the discrepancy between ethics and aesthetics, which doesn’t really need to be raised since I believe that a bit of morality is to be found in every poem or painting. On the contrary, I would claim that we are experiencing an overrepresentation of the ethical in the art world. You only need to look at the most important large-scale exhibitions. But an ever increasing number of public exhibition venues also see themselves as duty-bound to this approach. I view all of this as much too rationalistic, much too scientific. After all, art has nothing to do with knowledge, and knowledge has primarily nothing to do with art. I also believe that the gestus of the avant-garde – to equate itself with reality – has been exhausted. Often in exhibitions I can perceive no difference between journalism and art. However, with art – as I understand it to be – a window should be opened onto another world in which the laws of rationality are made powerless. I find that artists should advocate the aspects which they alone are able to do and not the aspects which they are also able to do.

K: Sloterdijk claimed years ago: “The modern work of art is a witness to the concept that human contributions to happiness are indeed possible.” However, according to him, this was only if they kept themselves outside of the realm of the art trade, otherwise they would “collapse”.

K: With all due respect for this thinker, I would still only conditionally agree with that statement because first of all I would distinguish between the work of art and the artist. A work of art cannot defend itself from being caught up in the art trade. However, an artist does have the ability to position himself according to the demands of the market. And speaking of the market, we have to mention the galleries. Without them there would be no market. Of course, the artist can – as often happens – continue to feed the market with more paintings without undergoing much reflection. But he can also observe this market from the corner of his eye, analyze it, and then continue working and making fine adjustments to his projects. For myself, I decided to produce fewer pictures – which are then produced more laboriously. Basically, there are not more than 8 – 10 works per year. I don’t do this in order to create a shortage. I produce fewer works in order to raise my work up to a higher qualitative level. Later, I am often disappointed in retrospect; that is what illusions are there for, to be disappointed. Still: all in all, it has been worthwhile to pause and reflect. But I basically consider the market – in order to come back to your question – to be the best place for judgment and evaluation. Incidentally, in financial economy, it wasn’t the markets which failed; it was rather the control mechanisms over the markets.

S: You could counter that by saying that the less acutely people are able to sense the “contribution to happiness” made by art, the more there is to be paid for it – in the form of an art subprime investment: there are only a few people who understand the investment, but everybody believes in vague ratings and thus in a secure appreciation in value. Does this not blatantly destroy the culture of receptivity which you have protested against, yet which is necessary for your art?

K: First of all I would like to advocate praising the distinction. With all due respect, your question is too imprecise for me. Certainly, there are only a few buyers of contemporary art who act in a self-determined manner. Yes, the majority of buyers is like the rest of humanity, not self-determined, always dependent upon the opinion of others, and continually confirming that humans are like sheep. The type of investor which you mentioned might have gotten cold feet in the light of the current situation and rightly justifies your comparison with art investments. However, there also exist some passionate art collectors of various professions who observe an artist over a longer period of time and purchase individual works at different points in time. These people fluctuate between being poor and rich. Their passion is collecting, real collecting, obsessive collecting, and it occurs not infrequently that this brings them to the brink of financial ruin. No question about it, many people would like to possess art, but only a few are able to do so. That is the way it always has been and the way it will always remain to be. Still, the wonderfully democratic approach still applies – beyond all categories of possession – that art – initially – is there for everybody!

S: The distinction is surely important, but would you go along with my claim far enough to assert that the social significance which art takes on is the result of staging by the media – with the well-known results?

K: No question about it, there isn’t anything I would say against that. In this context I would only critically add that there is not only mainstream painting, but there is also mainstream journalism which additionally cements this staging in the media. This type of reporting is not investigative work and uses unfiltered second- or third-hand information.

S: In your work there is a central significance to the depiction of relationships between people and to their surroundings which are indistinct, irritating, and usually latently threatening. What do you suffer from? Are you playing with the viewer’s fears of the abyss? Or does, in the words of Francis Bacon, “a really good artist have to …make a game out of the situation today”?

K: At the moment I am only suffering from your question. Do you really mean that a painter has to suffer in order to achieve a convincing portrayal?

S: To ask questions means to pose hypotheses, and there are at least three in the above question. What is so insulting about making conclusions regarding preferences in perception based on the moods in your paintings? It is neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for creative processes, but it is a possible one. So, the question remains.

K: I am an Epicurean. I am not a Christian. For that reason alone, I could consequently never receive strength through suffering. I have to be moved by the subject of the moment. And I achieve that only by being moved, which leads to a joy in realization. It doesn’t matter whether I am depicting something lighthearted or something tragic. Even if I imagine depicting the suffering of a crucifixion scene – even though you might ask what significance a crucifixion has in our times – this could only be realized – speaking for myself – with a certain joy. And in fact I believe that painters such as Ribera and El Greco in executing their crucifixion scenes and even painters like Grünewald in his portrayal of the Isenheimer Altar must all have felt joy, otherwise this suffering would not be able to move us as it does. When my father died, I also believed I had to overcome my suffering through painting. As a result, nothing was created, not one page, no paintings at all. The suffering was so great inside me, because with the loss of my father I had also lost a friend and I was basically at a loss for words, without language because mourning demanded too much from me to be able to evoke an appropriate form. Today I know that you first have to get through such situations before they can take shape. People who suffer make others suffer as well.

S: Let’s return to the topic I brought up before regarding the indecipherable web of relationships between the “acting” characters in your paintings. You often emphasize that formal questions such as light, color effects, composition, etc. take precedence over the emblematic configurations in your work. Is it possible to separate these elements?

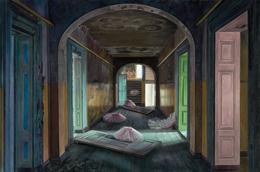

K: Well, the characters are also a part of the composition, but I believe it’s basically true that the individual questions regarding the formal composition of the painting are more urgent, even though I would admit that my paintings have become more narrative over the years, or at least allow for a certain interpretability. However, the severity of the background of the painting has always remained the basis, the foundation which often creates the starting point for these frequently ambivalent webs of relationships between the characters. This background is more than a mere stage, since the background of the painting opens up more in-between spaces during the course of painting. And these in-between spaces have – in a formal light – the same significance for my work. In these in-between spaces I often vary my painting; if one part of the picture is painted more liberally, this occurs when I have the intention of sinking my teeth into another part of the picture, in order to solidify it. And this oscillating between the possibilities is always present – to my chagrin – both in the design stage as well as in the execution of the painting. Creating a composition is frequently even more time-consuming than executing the painting itself. My goal is the construction of an invented microcosm, which doesn’t exist in our world, but which appears as if it really did exist. No, to return to your question, I don’t choose to become the henchman of that which we are constantly bombarded with in the press and media. One doesn’t become a painter because one has original ideas, because one has developed a certain attitude toward politics and history, which in any case is all too human. We can only find our place as painters when we develop a specific visual language. How else could a painter define himself? The subjects of paintings have never played a great role for me. There isn’t any subject matter which plagues me, and absolutely none which would be able to satisfy an academic’s viewpoint. The important thing is to persist, and this can evoke the most manifold elements. Also, I have nothing to say; perhaps that is why I paint.

S: You were born here and grew up here and you have experienced your artistic development for the most part here in Leipzig. Is there an explanation for you why such a biotope was able to develop here in this relatively small city?

K: When I began my studies in painting in Leipzig in 1992, nobody was interested in painting. I wasn’t able to sell a single painting during the entire course of my studies. And in spite of this, my decision to study at that unfavorable time was absolutely correct, because my financial circumstances forced me even more to drive my project forward, and it was that which made me robust. A different wind is blowing today at the Leipzig Academy of Visual Arts. The great majority of the students is lured by the promise of success, whereas true artists never question the conditions for art. At the Academy’s roundabout exhibitions, prices are occasionally negotiated, and one can often even find price tags, which I find intolerable. Of course, students of painting do require money to live on. The problem is only: If money comes before the actual design of the painting, then people who are on the course of a journey, and students – as all human beings – should be nothing else, will be less required to question themselves and their work. But I don’t want us to misunderstand each other: I don’t believe in the educational value of poverty, I only believe that a young painter should have to experience a period of humility, because a defeat has more power to bring someone forward than success, which often makes one frivolous. If you mature later and also have a little bit of luck, then you get everything back. And is there anything more beautiful in a human life than to pursue such an activity…

©2009 Stephan Schwardmann | Aris Kalaizis (Source: Magazin KREUZER 04/2009)