My Driving Force in my Impatience

An Interview between the philosopher Max Lorenzen and Aris Kalaizis about working abroad, loneliness, beautifulness and the unity of contrasts

Lorenzen: Mr. Kalaizis, you are associated with the New Leipzig School. Three years ago a large exhibition of your work entitled Ungewisse Jagden (Pursuits towards Uncertainty) was held at the Marburg Kunsthalle from March 18th to May 5th, 2005. In 2006 the Maerzgalerie in Leipzig hosted “Rubbacord” with works completed or at least conceived in the USA in 2005 during the course of a work-abroad grant and which will also be on view in New York in 2007. And also in 2007 you will be taking part in another work-abroad grant in New York. Let us first take a look at some of your work which was completed in 2006 such as The Morning After (2006) or At the End of Impatience (2006). In my opinion these works, which were painted back in Leipzig after you had returned from your stay in the USA, represent both an formal expansion and a compression of the themes you deal with. Was 2006 a decisive year for you?

…I realized how clearly this new threshold-breaking experience would affect me

Kalaizis: I wouldn’t go that far. But my stay in the USA was definitely a time that was rich in experience. You have to take into account that I’m a rather settled person and that at the time when I was thinking about the upcoming trip, I felt more worried than excited. On the one hand it’s because I don’t like to be so far away from my family and friends. On the other hand I was thinking to myself – there’s still so much left to do here, so many unresolved issues, and I can’t just shirk away from all of these prob-lems, because you take your problems with you on a journey, no matter whether you want to or not. But the main thing was that my stay in the USA was the very first time I had been alone in my entire life, and that was no small thing for me. If you have been living in a long-term relationship for as many years as I have, then there are many small day-to-day tasks that are shared. Often this is a relief, sometimes it’s a burden. It was only after I had arrived overseas that I realized how clearly this new threshold-breaking experience would affect me.

L: Could you please relate the most important visual and emotional impressions you received during you stay in America – you went to New York and where else did you go?

K: For the most part I was in Columbus, Ohio. I had received a work-abroad grant from the state Ministry of Science and Art and had prepared myself to work overseas – at least I thought I had. But then, immediately upon arriving abroad, I felt it was impossible for me to work there. I also felt homesick, but this initial homesickness, gradually faded away once I had begun to work. And I definitely did not feel like transforming the ideas which had begun formulating in my head back in Leipzig into paintings by working on them in Columbus. At that time I thought, just like I often say today: you have to give it your all, otherwise you will degenerate. For me ‘give it your all’ meant and still means taking risks, being open to what is new and different, diving into the forms and shapes of the new environment.

So I rode around on my little bicycle through the American landscape, wandered about using my legs and especially my open eyes, and during this time as well as shortly afterwards I felt rather frustrated, because I felt I wasn’t able to find a gateway into this place, into the environment. But fortunately this proved to be a misapprehension, since in those first days I had apparently been extremely concentrated during my travels through the area, because all of the paintings I created in America are based solely upon the intense observations of my initial days there. At the time I noticed – and I was able to use this observation later – that urban architecture in America incorporates significantly more round forms, which interact with strict, straight lines and it seems to be more well thought out than European architecture, which increasingly strikes be as being more angular. In any case these experiences must have been so deep and so concentrated that after completing a first, small oil painting, several others soon followed, which, as I just mentioned, were derived from my memories of my first days there.

L: If I may venture to say so, your American paintings appear to be in a relatively continuous line with your previous work. But after that something seems to have changed. What is it?

K: …Yes, I would certainly hope so. Striving for change or rather the intention to improve yourself is an almost holy ideal for me. I strongly believe that people were created and put into this world as a rough draft, so to speak, and that we have to prove during the course of our lives whether we do justice to the idea of this human existence. In other words we have to gain experience so as to use up the wealth of idiocy which we possess. I do this, for instance, by painting. Thus, every painting is another form of idiocy. But one form of idiocy should not be repeated, and painting or any other activity should therefore be a process of exhausting the different forms of idiocy one possesses. After all we don’t have access to a wealth of intelligence, but rather to a wealth of idiocy. I paint pictures in the hope that one day I will have such a dearth of idiocy, that it won’t even be sufficient for my own needs and that in the end I will have come one step closer to my idea of an ideal painting.

…uncanny beauty

L: Your principles of composition have meanwhile become well known: You work according to photographs of rooms or places (such as deserted factory grounds in the Leipzig area, see The Great Hope into which you place human figures – who actually visualize what the room already contains. I quote ‘But in any case, this background, which I have elaborated in the painting ‘The Great Hope’ must have acted as a detonator. (Interview with the sociologist Jan Siegt, 2003, published in ‘Rubbacord’). And this detonation reveals something mysterious, which you call the ‘manifestation’: ‘when you notice that everything has fallen into place, and a moment of divine peace and quiet begins’ (Interview with Jan Siegt, catalog ‘Von unvoreiligen Versöhnungen’, (Of Gradual Reconciliation, 1997). And this is the moment of inspiration. Thus, the ‘characters receive their home’ (Interview, 2003). This home is apparently the opposite of what one normally calls home –

K: Yes, according to Carol Strickland’s recent writings, it is a home which is furnished with an eerie beauty. But when you say I work according to photographs, that is absolutely correct. And I mention this because it often irritates me, when people comprehend that I work according to photos, but then immediately label me as a photo-realist. I deeply mistrust individual photographs. I have never painted a picture that solely relies on one single photograph. The photo-realists work in this way. I admit a photograph can come very close to what we call reality, but that is not what interests me. On the contrary, I contend that my work is a search, an eternal meandering through areas I haven’t yet contemplated or occupied. You must understand that in all of my paintings there are those shady areas of transition.

…I deeply mistrust individual photographs

Shady in the sense that they do not support or complement the central composition I have painted, but rather lead away from it. You could say that this is another form of postmodern random-ness which is so common today. But believe me, this process of brooding over painting compositions tortures me through several nights; it tortures me until the only true solution finally appears on the horizon. As a result of this search it is also possible that a seemingly irrelevant triviality will be produced, but even this has its justification, no, you could even say it has its necessity, if it is placed next to a moment of central significance in the picture. Something can gain significance only if it is different. And you have to utilize these differences sparingly.

But that is the most difficult thing of all! Perhaps I should speak of the correct extent, which is more urgent than ever, in painting, in film, in all aspects of everyday life. A father who raises his children only by using strict methods is to be judged just as harshly as one who constantly gives in. The reality, in order to come back to your question, or that which seems to me to be reality, is not what I find interesting, since I will be formed by it regard-less of what I do – whether I want to or not. Painting offers me a wonderful opportunity to redirect reality. Accordingly, I can only accept an art which offers me designs of another world. Of course, I am often disappointed, especially when I stroll through exhibitions, which suggest a context of knowledge and science. This makes me feel like I could puke, because I realize that my only capital, my eyes, won’t take me very far. Then I usually feel sick, because I realize how dumb I actually am. I have nothing to say either – maybe that’s why I paint.

L: The space which inspires you always contains something ambiguous? Just look ‘The Night on Every Day’: Dark clouds gather on the left and the woman who has been divided into two creatures incarnates both areas.

K: Perhaps this is an essence of myself, so to speak. In my preparations for a new painting I often journey to and fro between the most diverse possibilities. Of course in the beginning there is always observation, which is rarely sufficient. Something similar to reflective thinking results from this process, which is often derived from a possible discontent anchored within me, which drives me, and yet which is insufficient to exist by itself, and which thus needs to be led into a third dimension, which can exist on its own – and this is the actual dimension of painting.

L: Obviously the internal tension of your pictures results from the visualization of something that is invisible, in other words the mysteriousness or dichotomy of our existence. We can – we need to discuss such conundrums – they only become real when they are solved in a dialog, but unlike crossword puzzles they become intensified through this process. Do you feel you enter a danger zone when you conceive and work on your paintings?

…at least two designs, which constantly call for anarchy within me by propagating an unfathomability, which neither exists in my paintings nor in my life

K: I don’t mind, I even like the idea that the observation entails a certain amount of work and effort, which might lead to danger. However, my danger zone when working on a new picture is my doubting. It is this doubting, this constant opposition that I feel in myself, which is the cause or perhaps the blame for the fact that my paintings are the product of at least two designs, which constantly call for anarchy within me by propagating an unfathomability, which neither exists in my paintings nor in my life. These paintings are serious, they are funny, but often they contain a sense of irritation. In themselves they don’t demand anything in particular, but if you want to understand them, you need to be willing to be at the mercy of their spectrum of meaning, just like being on a swing, which you can only enjoy if you go along with the movement. Otherwise you will become nauseated.

L: In other words, if you don’t subject yourself to this danger, if you don’t step over these borders, you won’t be able to enter the dimension of true painting, but will rather only brush on the surface of that which we call reality?

K: Isn’t all painting real? And if this is true, then we have to ask ourselves: What turns a picture into art and why is another picture mired in eternal insignificance? However, you might be quite right. Taking a risk or entering a danger zone as you mentioned before, this only exists for a painter if he does not repeat himself in his painting, but rather risks everything by giving it his all – even if this might result in failure! Thus, we come back to the topic of taking “risks” and committing acts of “idiocy”.

It’s true that I can imagine the picture that I am going to paint three or four years from now. But that is just a vague impression, which I cannot explain at this point. This is more of a conjecture than a cer-tainty. A conjecture of something that does not exist, but which might come into being, has driven me from the beginning. My main drive is my restlessness. I am also not pursuing a goal. As a result I still have the feeling at the age of forty that I’m at the beginning phases of my development.

L: Let’s turn now to your most recent work. Let’s begin with some paintings which I found downright shocking. ‘The Morning After’ (2006) – the title which inevitably evokes ‘The Day After’ (1885) by Edvard Munch – depicts a young girl only dressed in her underclothes, who is seeking help but not receiving it from a woman who might be her mother; to the right and a bit in front of them a man is kneeling who is looking at his hands, and whose facial expression has something diabolical about it. The viewers are actually forced to think of an incident of incest – aren’t they?

K: Obviously, in painting this work, despite its shocking elements, I did something wrong. If the viewer is forced to think in only one direction, then this applies even more. Yes, the man is kneeling on the floor and is looking at his hands. I don’t think there is anything diabolical about him. When I painted him, I made an effort not to stigmatize his facial expression. The apparent harmony of the mother-child relationship on the left side of the painting actually screams for a projected counter manifesta-tion, a polarization which is based on this man. It is probably this mother-child configuration that makes us see something diabolical in the man, because it is actually us, who wish to interpret him in this way.

And I admit that this suspicion might be reinforced by the lighting dramatization that has been executed. But the hard lighting does not hit the man from the left side, but rather comes from the right, and as a light source I painted that monstrous refrigerator. But why is this damned refrigerator placed there, which for some strange reason you can’t look into and which moreover seems to supply inspiration? A child is searching for protection, a man comes under suspicion and a woman almost seems to radiate even less energy than the refrigerator. In other words this refrigerator is important and without this monster I probably wouldn’t have painted the picture! Of course, the refrigerator, which could also be labeled a poison cupboard, could have been opened up a bit more. But I didn’t want to do that, since I am almost fearfully mistrustful of any kind of pushiness, which I cannot tolerate in other pictures, of course, and which I can least tolerate in my own work. That is why my paintings never contain any blood, let alone a corpse, since I prefer to create a suggestive background noise, a hovering insinua-tion.

…this decision would not simplify our lives at an existential level

L: Another work ‘At the End of Impatience’ (2006): A young girl, wearing only underpants is lying on a rumpled bed; prompted by the title of the work the viewer makes the association of a first sexual contact – the same girl is standing to the right, separated from her counter-image, almost like a soul separated from its body, which is brooding about what has happened to her: the embodiment of mel-ancholy and perhaps of injury. The doppelgänger motif especially enhances the solitude of the scene. To ask you a direct question: do you believe that our longing for togetherness only intensifies our soli-tude?

K: I believe that is a fine observation, that the doppelgänger motif can clarify our solitude. As you know, I have been pursued by this doppelgänger concept for some time now – I would say for about ten years. It often appears and in this rather small picture “Am Ende der Ungeduld”, it has almost been taken to the extreme, since everything seems to be doubled in this work. And despite this, I think a heterogeneous picture has been created. But to come back to your question: I’m not sure if I as a painter can satisfactorily answer your question, which might also be seen as a thesis.

In any case solitude is a well-known state for me, since it characterizes my life as a painter. The only thing that is important for a human life is that solitude is a desired state and that it doesn’t become your undoing. The studio is my retreat, my reservoir, my private church if you will, since I would otherwise find everything to be just too much and life could overwhelm me. That is simply necessary for my existence.

As a philosopher, Mr. Lorenzen, you will have similar feelings. I don’t think that a person becomes a philosopher, for instance, or a painter because one continually tries to populate the solitude that is inherent in all people. On the other hand paintings, writings and so on, are ways to communicate which allow you to enter into a relationship with other people. Jean Paul has said this very well: ‘Books, novels are thick letters to friends’. One might complete this sentence by saying: …friends that you haven’t met yet.

Mr. Lorenzen, you were drawn to philosophy as I was to art. Both of us made this decision in the knowledge that this decision would not simplify our lives at an existential level, but would have the opposite effect of making it more complicated. That was completely clear. We made a conscious deci-sion to live a life burdened with more anxieties. Or do you believe that when I first started to study art back in 1992 in Leipzig there was anybody left who was interested in painting? Furthermore: deciding to become a painter in the time directly after the East German wall fell was considered to be insane in the eyes of many people. If you walk through this same academy today, you will quickly realize that another wind is blowing. And yet I am still happy that I entered the Leipzig Academy at that time and not today. Granted, that time was full of humiliations because nobody was interested in my paintings. However, on the other hand this situation was important since it toughened me up by forcing me to drive my own projects forward. That’s why present-day Leipzig would not be a good place for me to study painting.

L: The ambivalence of our existence is expressed in all of your pictures. There is a ‘great bestiality which rules inside all of us’ (Interview, 1997), the longing for the opposite – and for you especially, the longing for the ‘inner joy’ which art imparts to the viewer and surely most strongly to the painter through the process of painting itself: ‘Art is always joy, whether I represent something joyful or something tragic’ (Interview, 2003). Do we come closer to the ambivalence of life if we comprehend and feel that it simultaneously consists of joy and sadness, neither existing without the other, that each even requires its opposite?

K: Recently, and this almost goes back to the question of solitude, I was walking around in the woods without a particular destination in mind. Suddenly I came across an older man, whom I though was just wandering around as I was. When we came closer to each other I could see that he had these strange earphones in his ears and was listening to music or whatever. It seemed that he wasn’t able to hear the rustling of the leaves or the chirping of the birds. Either consciously or unconsciously he had denied himself the chance to enjoy the peacefulness, not to speak of the silence, of the surroundings. I thought to myself that this state of graceful peace might be something intolerable for him. You can’t just turn on the lights when you go to the movies. And yet, apparently for this man, as it probably is for more and more people, the knowledge of the mutually arising dualities which touch the founda-tions of the world are contemplated less and less or not at all. Incidentally, I have also noticed that there are certain films which have become old-fashioned because they are slower and more difficult to view, more difficult to consume. This comes to my attention especially when I lend films by Angelo-poulos say or Wenders or Jarmusch to friends or acquaintances for them to watch and they can only appreciate these films in the rarest of cases. And if they are watched, then not with the necessary concentration. Perhaps our viewing habits are changing due to the internet and television – I don’t have any idea. On the other hand a discrepancy opens up for me because I feel more clearly than ever how important a slowing down of pace is for my life and for my work.

L: Real (or now: postmodern) philosophy investigates this connection as does painting, this simultaneous existence of bestiality and joy and attempts to bring both before the inner eye in an intellectual outlook, as one used to call it. And now, if you will allow me to make a suggestion, why don’t you and I take a look at your ‘Nike’ pictures (2006). The first one looks like a variation of ‘At the End of Impatience’. The young, practically unclothed girl appears exhausted and is lying on an armchair in a pose which almost forces the viewer to become a voyeur. ‘Nike II’ might be a representation of her doppelgänger. She is cuddling against the armrest almost as if it were a human being; and yet, there is no connection between this child-woman and the piece of furniture: she rejects it in exactly the same way as she does her mother (only upon closer examination do you realize that the body, head and arms of the girl make no impressions upon the leather material of the armchair). If you view the pictures again, a feeling of eerieness arises. And it is just for that reason that you feel, at least I do, something like emotion in view of the self-abandonment of this body.

What a mixture: In this abandonment, this unconcern with respect to coldness and strangeness, a strange beauty arises, which is not abolished due to the admixture of lasciviousness, almost of ob-scenity. – I feel inspired looking at these pictures and believe I can perceive something of the joy you spoke of; but I am – almost – forgetting my question, which is: Doesn’t the creation of such a proximity between beauty and coldness (which do not offset each other in an ostensibly higher synthesis!) create the basis for a current, post-modern aesthetic? And moreover: What would you consider beauty to be today, in our post-modern age?

K: I’m pleased to hear whenever a viewer senses something of the joy that I feel when I painted a picture. And I’m even more pleased that your joy did not appear immediately, but rather upon a second view-ing. Yes, my daughter Nike, whom I painted in the two pictures possesses a sacrosanct beauty. But you can’t produce great paintings with such innocent purity alone. We then return to my inherent doubting, which finds expression either consciously or unconsciously. Just as it generally gives me trouble, Mr. Lorenzen, to render an account after the event of what I once painted, because first of all each picture created is often too complex to be able to explain it exactly, to be able to represent the motivating forces plausibly. On the other hand this would also mean rendering an account of a largely non-rational process, which is what painting is after all.

L: Let me ask you again: What does beauty mean to you today?

K: The Zeitgeist has gotten used to the idea of viewing beauty as an absolute value in an isolated way. There won’t be many people who recognize a motif of beauty in the simultaneous proximity of warmth and coldness in the two Nike pictures, which you have just described. If, for instance, coldness is claimed to exist in a picture, the concept of beauty is often filtered out, so to speak. On the other hand if you look at a picture by Corinth, let’s say the work ‘Cain’ (1917) or Ribera’s ‘Ixion’ (1632), you can easily grasp that these two works stand out due to a certain aggressiveness. They are tremendous in the truest sense of the word and impress the viewer with an apparent ugliness. Neither of these painters found their place by consciously painting something ugly. They painted these works since both the state of ugliness as well as beauty speak from within them. Following this impulse, these painters were able to create great art.

Consequently, ugliness is something which absolutely needs to be added to the idea of beauty. If this correspondence between these polarities is entirely missing, the result would be kitsch – consisting of beauty alone or of ugliness alone. The decisive point is basically an intellectual requirement. Of course painting will always be measured according to the soundness of craft. That has always been the case and will always remain the case. But craftsmanship alone won’t do it, because, as we already know, art does not arise from skill alone.

On the other hand if you contrast Corinth’s and Ribera’s work, for instance, with the work of two cel-ebrated contemporary painters such as Alex Katz or Norbert Bisky, whose dazzling works are in great demand among quite a few collectors who pay enormous sums for them, you suddenly get the feeling that you are looking at carnival paintings, because these mediocre painters create works in which any resulting interaction involving the nature of beauty is either underexposed or entirely missing. This is true for both the composition as well as the execution. All art strives for beauty. Of course, these two contemporary painters strive toward beauty as well, even though it must be established here that nothing can arise out of nothing. I would think that real beauty seldom comes alone, it absolutely requires an opposite.

L: Could that be a great goal of painting today, to search for the conditions and possibilities of a new beauty and to depict them?

K: I’m afraid I won’t be able to answer that. Every picture by a painting artist is always an expression of its specific beauty. Your question can only be answered in time, since while an artist may have access to a framework of composition, the conditions for this are presented by society on the one hand and by art history on the other. Therefore, we are not as free as we believe. But during the course of our lives we have at least the chance to liberate ourselves. And that is something!

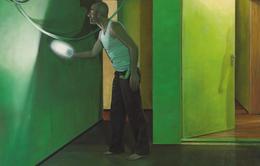

L: Perhaps we both work, if I may venture to say, on the same issues, each in his own way. The old (modern!) fear that painters and writers had of speaking about their work is outdated. That is why we are talking with each other. And we are not practicing art history here and are not planning to dissect concepts but rather are attempting to communicate on the new conditions for inspiration, because the-se have a direct effect on us. In ‘Deafcon No. 1’ you portray yourself at work. But you are not standing in front of an easel, but are rather standing directly in front of an indoor wall and are holding a – what in your hand? In any case you are looking at the empty, strangely glowing surface in front of you with extremely rapt attention. What are you looking for?

K: I’m just holding a lamp in my hand.

L: The new attitude to life, which you help to articulate in your paintings, is based neither on the mere ‘aversion to existence’ nor on an ‘unlimited affirmation of existence’ (Interview, 1997); it contains both simultaneously. Is such a parallel perception the requirement for perceiving the intensity of reality and for allowing yourself to paint in such a way (‘Is it me who is painting? Are there whispers in my paintings trough the trees, through the wind, of earth, of one’s sex, of history?’ ibid.)? Does such a perception require a particular level of alertness? If yes, how does one reach such a state?

K: As far as I’m concerned alertness, as you describe it, is definitely required, which brings us back to the required concentration we spoke about in the beginning of our conversation. The search for a spark-inducing beginning can sometimes be discouraging and sometimes encouraging. There are days, such as those in Ohio, when one beginning triggers the next and the next almost like a chain reaction. Then there are days when nothing happens, when I have trouble finding something like an inner peace. Then I usually run around like a moron and try to amuse myself, do projects at home, run around with an electric drill in my hand or pound nails into the wall. But these are just excuses for activity more or less. Basically, it is just another, rather inelegant form of waiting. You can picture it as waiting in a dentist’s waiting room, except that I’m both the patient and the doctor.

…my waiting consists of an absorbed pausing which has the goal of finding intransi-gent precision

On the other hand something is changing within me regarding my finding subjects to paint, because as you know I used to have to observe my immediate surroundings first. Today I sometimes have entire pictures dancing around in my imagination, without my ever having laid eyes on any part of this image or to describe it better: vision. This makes the execution more difficult, as you can imagine. In any case I can say that my waiting consists of an absorbed pausing which has the goal of finding intransi-gent precision, until you see the supposedly right way to proceed. But even if we believe we have found the right way, it is only one side of the coin. the other side is then decided on the canvas.

L: Let me ask you another direct question: Where do you find your models, and why is it that your wife and daughter appear so often in your work?

K: That is more a question of convenience. I know their physiognomy and they know my psychology to some degree. It is a kind of unspoken agreement, which I also fall back upon when painting the other figures, who are all, as you know, friends and acquaintances of mine. I appreciate this circumstance, since it simplifies many things.

L: Let me ask you a completely different question now that we’re coming to an end. You could be ascribed to the Leipzig School, which has been receiving great attention on the art market for some years. Does this state of being “in” signify a challenge for you, a motivational push, so to speak, which enables you to push the envelope? Or are there other reasons for the fact that your paintings have in-creased yet again in riskiness, not only thematically but also formally.

K: On the one hand of course it’s very pleasant for a painter to be able to live from his work. However, just because my life before was more worrisome than it is today, it doesn’t mean that it was less worth living, because I felt and still feel that there is nothing more wonderful than the act of living a human life. I’ve always felt this way!

On the other hand it is important, especially when things appear to be working out more easily, to work with at least as much and perhaps even more concentration, because success, if you choose to call it that, can quickly make you careless. My yearly production of paintings amounts to around ten to twelve pictures. The trend is falling – to the chagrin of my gallerist. That means, you have to find your rhythm, otherwise the art market will devour you at an existential level. In any case, I believe that a painter’s existence should include a moment of internal resistance, which should be strong enough to counter what is marketable. Even starting from a state of well-being, a painter must develop resistance and, of course, he must overcome this in the end – only then can he have the feeling that he exists.

However, if you look at the contemporary art market in the last few years, for instance, you will have a hard time overlooking the fact that the majority of the creators of art learn about the demands of the market to a certain extent. Of course there is more painting going on today. But that alone does not suffice to justify the assertion that this is being executed at a higher level. In this I am trying to castigate the basic connecting correspondence between culture and commerce.

This rather concerns the question of priority. Is a painting determined by its contextual, i.e. formal content? – Does the question of demand therefore take a backseat or do sales figures determine what is being painted? You don’t have to take a look at mass media alone, the cultural milieu is sufficient, in order to obtain a clear picture of the incredible commercialization and evening out that is taking place. Thus, the multitude of paintings has not produced variety, but rather an increasing uniformity. A mael-strom of the agreeable, of the entertaining is spreading out everywhere. However, I would like to add that there is nothing to be said against entertaining elements, because there should be a moment of joy or fun in every work, since it this which makes the activity interesting to us, after all. It only becomes critical when you attempt to subsume your entire doings solely under elements of fun. When too much is omitted, something cumbersome is undertaken.

L: Would you ascribe yourself to the Leipzig School?

K: No, I’m not a representative of any kind of school or label. I’m my own representative.

L: You admire Ribera. Which painters of the past – and the present – are of particular importance to you? What kind of literature, which authors, do you read, which music do you listen to, which films do you like to watch?

K: Bacon, Hammershøi, Rauschenberg are great! I only listen to music in my studio. This is of a harder variety and full of tension, because it best reflects my stress ratio while I’m painting. I’ve already mentioned a few film directors. But there is one, Christopher Nolan, I’d like to particularly mention. His films are my favorites, from the first (Following, 1998) to the most recent (Prestige, 2006). Even his earlier, low-budget films are thought out in an intelligent and engaging way. He executes enormous twists in his movies, demands much from his observers or viewers and can realize intellectual leaps in a formal way, which is even more important in film making.

At the moment I’ve been reading much too little, unfortunately. My reading matter is also not very diverse – I tend to reread material. I mostly do this in the evenings, before I go to sleep, so that I can soon drift off, inspired. At the moment I’ve primarily been reading, ‘Rameau’s Nephew’ by Denis Diderot again and again, because it is a book with many stumbling blocks.

©2007 Max Lorenzen | Aris Kalaizis

Max Lorenzen, born in 1950, was a philosopher and a writer, as well the founder of the Marburger Forum. His publications include "Das Schwarze: Eine Theorie des Bösen in der Nachmoderne. Eine Idee der Aufklärung" and "Krankheit. Kälte. Unsterblichkeit: Drei nachmoderne Erzählungen". His most recent work is on a "philosophy of postmodernism". Max Lorenzen died in Marburg 2008.