Comments on the Messianism in the Oeuvre of Aris Kalaizis

Prof. Dr. August Heuser signs in his essay a parallel between Paul Klee " Angelus of Novus " and Aris Kalaizis' image "make/believe". In it he subordinates among other things to both artists a messianic impulse which rebels against a materialist historical understanding.

The question, what reality may be, has been answered frequently and variously, but it still remains as one of the most difficult questions in the history of philosophy. What is it that »whatever holds the world together in its inmost folds«? How, one may ask, is reality constituted and constructed? From where do we gain certitude in our world? Of course, the answers given are altogether ambiguous and only few answers are indeed convincing, albeit positivism and materialism have tried to persuade us otherwise.

Sottorealism

In the idealistic-platonic tradition of philosophy, reality is constituted from above, from an idea downwards. The word metaphysics may also be translated as after, behind, or beyond physics. According to that rationale, philosophy assumes that it must be supernatural, if a thing does not enter into the world as phenomena. What Jewish theology calls messianic is always something promised and providential.

In the publication »Rubbacord«[1], the American art historian Carol Strickland, while discussing the work of Aris Kalaizis, refers to the British author Harold Pinter whose drama makes »dark allusions and gives impulses laden with meaning« aimed at leaving the audience in a state of uncertainty, in which they »supposed to arrive at their own conclusions.« Somewhere else she says, the beholder is invited by the artist to »search beneath the surface, to immerse themselves in the hidden allusions like an archeologist searching out traces of a past civilization.« This subaltern world she calls »Sottorealism.«

Using the term »sottorealism« we may apprehend all that which lies beneath reality, what is not reality constructed from above, but what is sustained from beneath and makes everything possible from there. We are, so to speak, talking about the basic structures of reality, its grounding, and – quite literally – its foundational conditions. In saying that, we must ask the question whether it is possible that reality is not only constituted from above, but also from below. Since we have the term »surrealism« referring to the supernatural, we may now also inquire if »Sottorealism« aims at that which is beneath the naturally sensible and apprehensible. Goya's »Caprichos« are aimed in that direction. They uncover the substructure of being and show what reality draws upon, so that it may be real, and from where reality stems from, namely from the dualism of reason and fantasy. Using the title of the piece of art just mentioned, we may describe this situation a bit better: »The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters«. Is sleeping reason a precondition and could we thereby mean a precondition of reality, that is, is sleeping reason what lies beneath reality?

The Reality of Mankind and of Angels

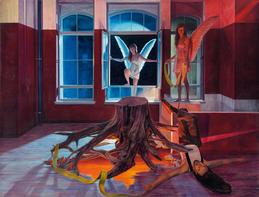

In 2009, Aris Kalaizis relied on two reality-makers – a photo he took himself as well as a photo he took from a newspaper. He made those two photographic images the point of departure for visual cosmos that is now titled »make/believe«. The painting shows Pope Benedict XVI. walking into a chamber through a wide opened door. The scene may possibly be located in the Vatican. He passes under a lighted dome, his arms spread out wide in order to greet – maybe a crowd of pilgrims or a delegation, or maybe only the beholder of the painting. Still in the doorframe, he is followed by three bishops, behind them various staff members. On the right side of the painting, we see a Swiss Guard, to the right we see the figure of an angel with larges wings dressed in an ordinary suit. The angel is a man strangely wearing contemporary clothing. While his left hand seems to be opening his shirt's collar button, his right hand is pointed harshly downwards to the floor.

The essential symbolic signals set in the painting come from the lighted dome, which spills light into the chamber from above. But the figure of the angel also gives us such signals by pointing downwards to the ground. Of course, the eye of the beholder will not find anything on the floor that may justify the angel's pointing down. What is the angel's motion aiming while it is pointing in the opposite direction of the light?

The picture's title »make/believe« cites two attitudes of human beings in the world on the one hand, doing and producing – to do things and to make things characterizes the material constitution of mankind and on the other hand, we have faith as the knowledge of spiritual things in the world. One is inclined to ascribe the heavenly light and the figure of the pope to the spiritual interpretation of the world. Faith is generally thought to be something concerning the heavens and cannot just be produced by humans – not even by the pope. It always stays a supernatural event. But the heavenly harbinger, the figure of the angel, we might want to attribute to a transient dominion, a place in between. He has come from the heavens, but he is motioning us towards earth. And in doing so, he is referring us to the place of creating and productive doing. It looks like we are able to gain some spiritual light from creating and doing things, and then the various spheres of heaven and earth (and hell) seem to somehow belong together – which would resonate with Pope Benedicts thesis that faith and reason belong together.

In 1920, Paul Klee drew his »Angelus Novus« – his »new« angel or »young« angel. Walter Benjamin bought this picture in 1921. Klee's wife Dora had given Benjamin one of her husband's drawings before – it was »Introducing the Miracle« (1919). This gift let Benjamin take note of Klee, and he would become an admirer of his art. Benjamin incorporated the »Angelus Novus« into his disquisition »Theses on the Philosophy of History« (1940) as the Angel of History.

Benjamin's disquisition is an essay in the history of philosophy or the history of theology. It makes a messianic claim. He argues against a materialistic interpretation of history and speaks about the messianic impulse within the history of mankind. The climactic tension built up by philosophy and theology also shapes the context of this painting by Aris Kalaizis – the tension between a papal figure inspired by the heavens and the Angelus pointing downwards to earth. Like Klee, the Angelus of Kalaizis refers to that which lies beneath, the netherworld, and tries to make sense of it. Both figures open up areas of perception and understanding.

Walter Benjamin's essay may certainly not be simply transferred fully onto the painting by Aris Kalaizis. But using it, we may find the trail of an abundant interpretation. It is indeed astonishing that Klee as well as Kalaizis have both made the figure of the angel fruitful when envisioning their pictures. In the case of both artists, the angel stands for his transient and intermediary qualities between heavens and earth, that is, between the visible world and the world unseen, between the world above and the one below, between yesterday and today – forever short of the future that wants to deceive us in believing in mere progress. The Angelus novus by Aris Kalaizis refers towards the foundation of that which makes up our world. Following this train of thought, the Jewish Philosopher Gershom Scholem, one of Walter Benjamin's friends, could interpret the Angelus Novus as a messenger of the Kabala, the revelation of the equivalent analogy of the above and the below.

Viewing the »Wunderbar« as Reality

The large-scale painting »Die Stunde der Entweltlichung« (2012) cites a word used by Pope Benedict XVI in his famous lecture given in Freiburg when he visited Germany in 2011. The German word »Entweltlichung« means something like de-secularize or de-worldfulness. Its usage caused an outcry, because it was understood as a message to the church and its representatives to refrain from secular structures and options and instead to turn towards more spiritual matters. According to that reading of the whole issue, it was about an opposition of secular and sacred realms, between the spiritual life of church and the secular life in the world.

Drawing on Klee's title »Vorführung eines Wunders«, we might also use the title for this painting. Aris Kalaizis depicts a bar room scene somewhere in the red light milieu that bears a signifying sequence neon letters in cerulean blue: »Wunderbar«. This reference is indeed ambiguous. The »Wunder« or miracle, as the proverb goes, is faith's dearest child. And the bar, on the other hand, is the quintessence of secular life: alcohol, debauchery, leisure time, self-centeredness, the world's vanity. The bar is, of course, also a place of yearning, a space beyond or outside everyday ordinary life, and without its commitments.

Two men are standing at the bar. The hour is probably an early hour in the morning. The day is breaking. The bartender wearing a white shirt has already cleaned off the surface of the bar. The morning newspaper is already lying on its top. Is there the silhouette of a cleric on the front page of that newspaper? A first or final glass of water has been poured for one of the guests. Opposite

the bartender there is the figure of a strange or miraculous guest, with long hair under his hat. He somehow seems to be removed from the period implied in the picture. He is wearing historical garments. His right hand is leaning on the bar, his left hand his pressing the head down onto the bar. Above him, a woman's body is floating without something that the painted wanted to be cut away – her head.

When looking at this picture, the beholder also will go away with a sense of an irritation. It is really »The Hour of Disembodiment« or in the German »Stunde der Entweltlichung«, the hour that is beyond or transcends the ordinary order of being. It is the hour of wonders that the artist brings before our eyes. It is not clear if the other two figures in the painting are actually realizing the miracle happening in front of them. But it is also not certain if the body floating out of the frame belongs to the head that is being pressed onto the bar. Many questions remain unanswered.

A lot of things stay in the open, despite the painter's masterly clarity that marks the paintings by Aris Kalaizis. The reality of these paintings is a reality that is left open. It cannot be pinned down or fixated, but is a reality into which »the splinters of the messianic have been strewn about«. What Walter Benjamin is saying with respect to history, Aris Kalaizis asserts in his paintings. He paints pictures beyond and outside the homogenous and empty imagery of his contemporaries. In every second – or applying Benjamin to this context: – in every square centimeter of his canvas there is »the little gate through which the Messiah may enter«. In that sense, his paintings are searching and questing messianic paintings, as Pius Siller said in another context. That is, they have meaning and refer to field of meaning beyond the ordinary constructivist tendencies of our thinking. He leaves reality open, so that alternatives may appear therein and wide fields of meaning, if we notice them or not. Airs Kalaizis foregoes the construction of reality as something already in definite existence. It makes me think of what the philosopher Markus Gabriel said: »I claim that existence isn’t the quality of objects in the world or within fields of meaning, but that the quality of fields of meaning is that something may emerge within them and through them.«[2] I call the ability to let meaning emergence messianic, and it is exactly what one may witness in the visual cosmoses depicted by Aris Kalaizis.

Prof. Dr. August Heuser was born in 1949 and is the director of the Dommuseum in Frankfurt am Main as well as the Museum of the Diocese Limburg. He has widely published on contemporary art and lives in Frankfurt/Main.

1 Aris Kalaizis: „Rubbacord“, Bielefeld 2006.

2 Markus Gabriel: „Warum es die Welt nicht gibt“, Berlin 2013.