The Home of Words

In a second approach to her trilogy, the Cologne-based psychoanalyst Fotini Ladaki, who practices after Lacan and Freud, examines the work of Aris Kalaizis from the perspective of a phylogenetic iconography based on the paintings "The Ritual" and "The Band".

"And God commands me to paint."

(Rilke: „Das Stundenbuch“)

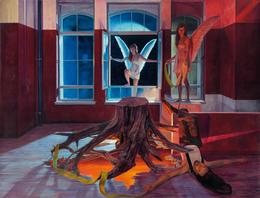

A huge tree root system in the middle of a living room. Behind an observing woman, in front a man in action: scene of a frozen snapshot. Many associations that evoke this image and the associated signifiers flow towards you. The signifiers also smuggle themselves into the dictum of popular wisdom. These are often rumored and maintained. Are the pictures "The Ritual" (2008) and "The Band" (2013) an iconographic depiction of one's own, incarnate roots?

Is it a matter of taking root, for example to be able to locate one's own family history, or is it a question of descent or one's own family tree? Is this cut-off stump in both paintings an imaginary-pictorial hyper-metaphor for lost roots?

History and ancestry are enormous pillars on which culture rests. There are different tribes and the stud book. If there were no tribe, there would be no tribal history. If there were no root, we would be uprooted. It seems as if the images run along a phonetic materialism or an equivocal (ambiguous) character of the words. It is not for nothing that Lacan derived the term materiality from the French word mot.

"Conversely, the point of view I am trying to uphold before yours entails a certain materialism of the elements involved, in the sense that the signifiers are actually embodied, materialized, that are words that walk and practice as such they perform their function of stapling.” Lacan J: (1997) The Seminar Book III. The Psychoses, p. 341)

If there were no root, we would be uprooted

Is Aris Kalaizis staging the phonetic homeland of words in these images? An unconscious motive could be the acceptance of the artist's own biography, which clearly goes in the direction of searching for one's own roots. But beyond the biographical traumatic material, Kalaizis possibly stages the topos of further universal phantasms of a world that is attached to the images and precedes the words. But which topos can be meant here? When you have abseiled from certain relationships and affiliations, you initially fall out of line. If the rope teams do not support, the connection becomes obsolete. One must seek and find a new bond in order to enroll in a new attachment or affiliation (home, family, group).

The content of Kalaizis seems to stem from a discourse that still has another hint pending from the materiality of the language and the signifiers. One could connect it with the world of ideas after Plato, which Lacan already tried to do in his seminar book XI:

"The image of the representative of the Leipzig school does not compete with appearances, it competes with what Plato represents beyond appearances and as an idea. Because the picture is that appearance which claims to be that which gives the appearance, Plato opposes painting as an activity rivaling his own." (Lacan J.: The Seminar Book XI, p. 119)

Both "The Band" and "The Ritual" seem to follow a trail that attempts to inaugurate itself as an acousmatic precursor of language. He stages the home of words. According to Lacan, this staged world can be attributed to the real. In the real, Kalaizis searches for the elementary materiality of language and stages it in an irritatingly grotesque realm of the real.

The real is incomprehensible and uncanny.

The real exists alongside the imaginary and the symbolic. Lacan speaks of RSI, which creates the equivocal ring of heresy. Perhaps it is a heresy, a contradiction of principles that have crept into the mind, which is now followed by a heresy of subversion, which in turn produces a translation and functions according to the Socratic laws.

So are these paintings also about heresy? A heresy that puts image above word and logos? Was in the beginning the image and not the word?

Seek a new scroll in a new affiliation (home, family, group)

Jacques Derrida also deals with the difference between phony and graphic as well as with the dominance of logocentrism in the western world. In his "Grammatology" he writes: "The nature of the phones (…) would be directly related to what in 'thinking' as logos is related to the 'sense', generates it, receives it, expresses it and 'gathers it together'" (p .24). And a little later, starting from the Kabbalah, he says the following sentence: "(…) the intelligible side of the sign remains turned towards the Word and the face of God … The sign and divinity are born in the same place and at the same hour. The epoch of the sign is essentially theological.” (p.28)

In Plato's Kratylos dialogue, Socrates also propagated a similar theory about the origin of concepts and language:

“So if the word is to be similar to the object, then the letters from which the root words must be composed must also be similar to the objects by nature.” A little later Socrates puts forward the following thesis: “Father 'Zeus' is obviously suitable whose name is wonderful, only it is not easy to remember. Namely, neat as an explanation is the name of Zeus; only we have divided it, and some use one half, and some use the other half.

For some call him Zeus, others Dis; but both put together reveal to us the essence of God, which, as we say, a name should be able to achieve. Because nobody is so much the cause of life for us and everything as a whole as the ruler and king over everything. Quite correctly, therefore, this God is named as the one through whom all living things boast to live. Just as I said, the name, which is actually one, is divided into dis, from through, and zen or zeus, from life”. (Plato: Complete Works, Volume 3, Rowohlt's Encyclopedia, 1994, p. 32)

So Zeus comes from the word Zoe and Zoe means life. Socrates also investigates the other names of the gods:

"There is no need to contradict Hesiod about 'Aphrodite', but one can concede that she was so named because of her origin from the foam of the sea, aphros".

Socrates not only sticks to the names of the gods, he tackles other things as well when trying to explain the originality of the words.

"Likewise, words would never resemble any thing unless that of which the words are to be composed had a certain resemblance to that of which the words are copies. But must they be composed of letters?” (Plato, Kratylus, p. 81)

Kalaizis now dresses the human trauma in the guise of a now figurative guise of the words: Uprooted, roped down, looking for the tribe, having a tribal history, belonging to a tribe? Does he thereby put the words in the place of the phantasm by neutralizing and recomposing the phantasm via the words? In the picture "The Ribbon" it is not the rope that pulls through the picture, it is the female angel who carries it through the pictorial space. Is finding a social bond an angel's work? Why the angels have to be female, let's put it there first. After all, and it should already be mentioned, we also find male angels in other Kalaizis paintings.

But does Aris Kalaizis lay bare the original acousmatics of the words and their origin in these two pictures, as if they point to an individual trauma? Or is the trauma pushed into a sacred place or into a strange garden of a real (Garden of Eden)?

Both paintings depict a feverish dream that arises when fundamental events such as attachment and home are threatened

In Greek Orthodox iconography there is Saint Christopher. This Christopher, however, does not carry Jesus on his shoulders as in the Catholic tradition. He carries Jesus within him. And he's a dog-headed martyr. Originally he is said to come from a dog-headed people on the outskirts of India. But because he learned the human language and passed his martyrdom, he was canonized. He is depicted in the garb of a general or a higher military person. But he always stuck out his tongue and looked up at the sky. But isn't the tongue also the organ of speech?

The images "The Ritual" and "The Bond" seem to reproduce a feverish dream that arises when fundamental events such as attachment and home are threatened. According to Freud, two more signifiers can be brought into play for the word homeland: the homely and the uncanny.

But in a time characterized by mass emigration and refugee movements, these two Kalaizis pictures in particular tell of the sphere where the nightmare and the fear of a lost home also constitute the shimmering of a floating hope. Both symptoms, fear and hope, coexist in a charged relationship that is ultimately unresolved by the painter. It is therefore up to us to transform this arc of tension into a reflex that is fruitful for us.

Literature

Derrida J. „Grammatologie“, 1983, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main

Lacan J. „Das Seminar Buch III. Die Psychosen“, 1997, Quadriga Verlag, Weinheim, Berlin.

Lacan, J: „ Das Seminar Buch XI. Die vier Grundbegriffe der Psychoanalyse“, 1987, Quadriga Verlag, Weinheim, Berlin

Platon: Sämtliche Werke, Band 3. 1994, Rowohlts Enzyklopädie, in Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg

Fotini Ladaki, born in Northern Greece in 1952, is a psychoanalyst (according to Lacan and Freud) and works in her practice in Cologne.

In addition, she works actively as a freelance author. In addition to many essays on art and psychoanalysis, plays, short stories and poetry, she also wrote an essay on Gerhard Richter “Moritz”. About the horror of the experience of existence or something like "Freud came to Parla-Dora". Her other publications can be found on the following website: www.praxisfls.de

©2017 Fotini Ladaki | Anna Popoulias | Aris Kalaizis